GASTROINTESTINAL OR GASTROENTEROPANCREATIC NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS (TUMOURS)

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumours or neoplasms (NET or NEN) are one of the rare tumours that affect the gastrointestinal system. Overall, they are the second most common digestive cancer. They can occur anywhere in the body.

NETs that arise in the pancreas are pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNET). Carcinoid tumour is another name for gastrointestinal NETs. Gastroenteropancreatic NETs (GEP-NETs) is a term that includes both.

These tumours arise from the enterochromaffin cells in the intestine and islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. These cells have traits of both nerve cells and hormone-making endocrine cells.

These are relatively slow-growing tumours compared to other cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. Overall, they have a better outcome compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, this is not always the case. Some neuroendocrine cancers can be equally or more aggressive.

CLASSIFYING NEUROENDOCRINE TUMOURS

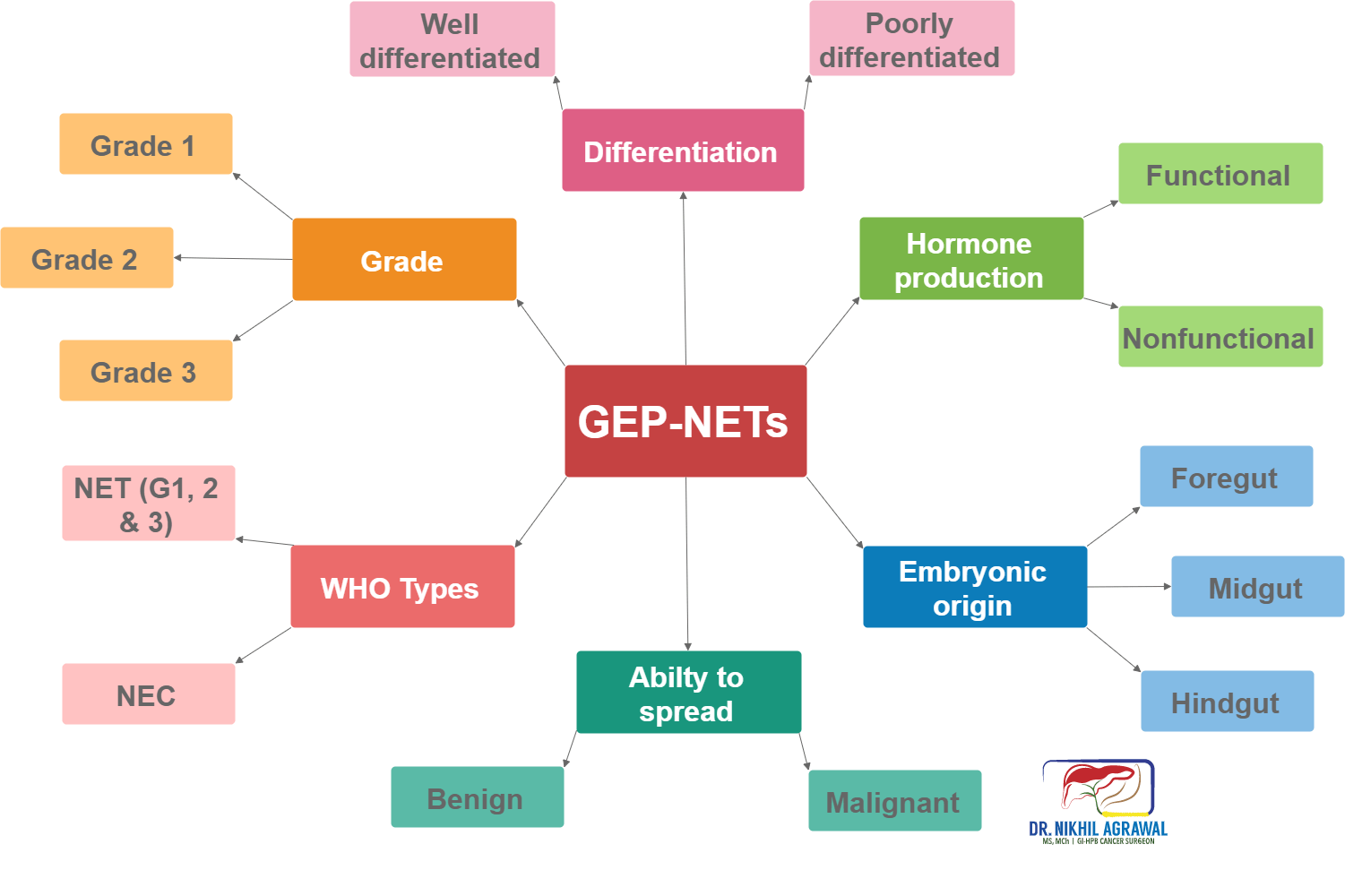

There are various ways of classifying neuroendocrine tumours. The classification depends on the organ of origin, grade, differentiation, aggressiveness, hormone production, and ability to spread.

Embryonic origin

Based on the embryonic origin, it classifies them into:

- Foregut (oesophagus, stomach, duodenum and pancreas) tumours

- Midgut (jejunal, ileal and caecal) tumours

- Hindgut (distal colonic and rectal) tumours

Hormone production

These tumours can release a variety of hormones and substances in the blood circulation. Hormones are substances which when produced and carried through the bloodstream, have specific effects on other cells and organs. GEP-NETs are classified into nonfunctional and functional depending on their ability to produce hormones.

- Nonfunctional: When neuroendocrine do not secrete these agents, they are termed nonfunctional.

- Functional: Functional tumours produce excess hormones or substances. Symptoms depend on the hormones they produce.

Nonfunctional tumours

These tumours do not produce symptoms until they grow big. The number of people diagnosed with nonfunctional tumours is increasing as the awareness increases and diagnostic modalities improve. Nonfunctional tumours have a worse prognosis compared to functional tumours because they manifest late. Between 60-90% of all PNETs are nonfunctional and frequently asymptomatic. Most intestinal NETs produce hormones, but they remain nonfunctional as the liver metabolizes these hormones.

Functional tumours

Functional gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours - Carcinoid syndrome

Many intestinal NETs (carcinoid tumours) secrete serotonin and kallikrein which produces this specific syndrome. It is rare with gastrointestinal and pancreatic NETs, as the liver breaks down these hormones and they do not reach the blood circulation. However, in those with heavy disease burden and liver metastasis, the capacity of the body to break down these substances is overwhelmed and carcinoid syndrome occurs.

It manifests with skin flushing, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, vomiting, breathlessness, wheezing or asthma-like symptoms and heart failure. Our body breaks serotonin into 5- HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid). A useful initial test to diagnose carcinoid syndrome is the 24-hour urine levels of 5-HIAA, which is raised in these patients.

Functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours

The functioning pNETs make up about 30–40% of all pNETs displaying nine different clinical syndromes: insulinoma, Zollinger-Ellison, Verner-Morrison, glucagonoma, somatostatinomas, ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTH-rP) syndromes. Some patients might also present with carcinoid syndrome.

Insulinoma: Insulin is a hormone produced by cells in the pancreas to regulate sugar levels in the blood. Tumour of these cells is an insulinoma. Excess insulin causes low blood sugar levels which causes lightheadedness, blurred vision, weakness and confusion. These are usually slow-growing benign tumours. Insulinomas are the most common functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Gastrinoma: Gastrin is a hormone which causes the stomach to release acid for digestion of food. Gastrinoma is a tumour of gastrin producing cells. Excess of gastrin prompts the stomach to release enormous quantities of acid. Most gastrinomas are cancerous (malignant) and occur in the pancreas's head.

Glucagonoma: It is a tumour of cells producing glucagon. The function of glucagon is the opposite of insulin. Excess of glucagon results in raised blood sugar levels. Most are malignant and occur in the pancreas's tail.

VIPoma: Tumours that produce vasoactive intestinal peptide.

Somatostatinoma: Produces excessive somatostatin.

Ability to spread

- Benign

- Malignant

They can both be cancerous (ability to spread - malignant), or noncancerous (grow but do not spread to other organs - benign).

Differentiation of tumour cells

Differentiation refers to the extent to which tumour cells resemble their normal counterpart. Differentiation classifies tumours into:

- Well differentiated neuroendocrine tumours: These tumour cells more closely resemble their cells of origin.

- Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumours: The cells don’t look like normal cells.

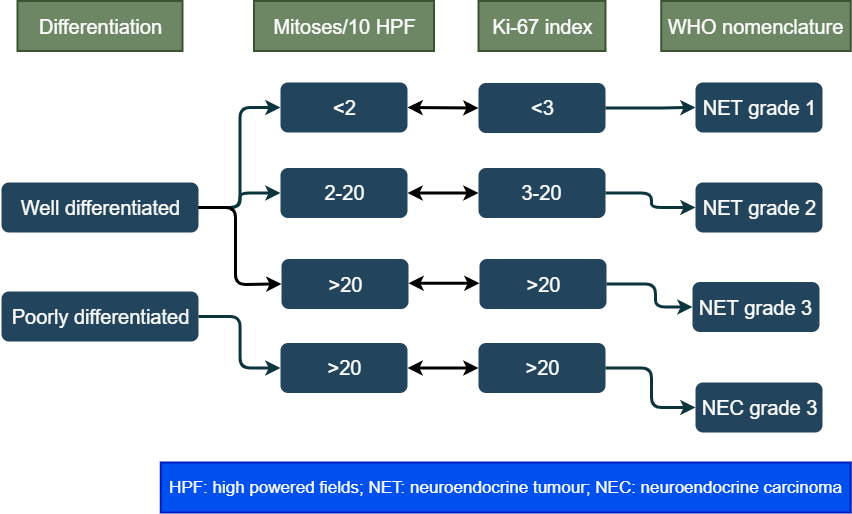

Grade of tumour cells

The tumour grows by cell replication. The cells replicate by constantly dividing, and producing more cells, a process called mitosis. The grade is a way of measuring the rate of division. It is measured by counting the number of mitosis under a microscope (mitotic count) and Ki-67 index (a protein in the dividing cells). The higher these numbers more the cell division and higher the grade. Between mitotic count and Ki-67 index, the higher number is taken. The tumour is then grouped into three categories based on these numbers:

WHO classification

The world health organization combines grade and differentiation to classify these tumours in four types. This is the most important classification of these tumours.

RISK FACTORS AND CAUSES

DNA of a healthy cell sometimes develops a mutation in the process of cell division. This leads to uncontrolled growth of cells forming a tumour.

A risk factor is something which increases a person's chance of developing a disease. It does not directly cause the disease. Some with many risks factors will not have the disease, while some with no known risk factor will get it.

Some risk factors for neuroendocrine tumours include:

- Family history of neuroendocrine tumour

- Smoking

- Heavy alcohol use

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Being overweight

- Excessive coffee intake

Having certain preexisting syndromes increases the risk of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. However, most of the NETs are not related to these. Examples of such syndromes include:

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1 (MEN 1)

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2 (MEN 2)

- Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

- tuberous sclerosis complex

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Tests done for unrelated symptoms detects many neuroendocrine tumours. This is especially true for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Symptoms occur, depending on the location of the tumour in the gastrointestinal tract and production of the hormone.

The tumours which do not produce hormones (nonfunctional tumours) rarely cause symptoms until late. They are mostly detected unexpectedly. They cause symptoms when they grow large. These symptoms could be pain abdomen, fatigue, unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, change in bowel habits or lump anywhere in the abdomen.

The tumours which produce an excess hormone (functional tumours), reveal themselves through the effects of those hormones. The symptoms in them depend on the hormone produced.

Small intestinal (bowel) NETs

Most originate in the last part of the small bowel called distal ileum. These tumours present with intermittent cramps, abdominal pain, weight loss, bloating, diarrhoea, black stools or vomiting. If it grows large enough, it can cause complete blockage of the intestine (intestinal obstruction). Many of these tumours produce hormones but carcinoid syndrome does not occur as liver metabolizes these hormones.

Gastric NETs

These are Neuroendocrine tumours of the stomach. There are three types of gastric neuroendocrine tumours.

- Type 1: Most common type (80%). Occur in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis because of excessive gastrin. These tumours are often slow growing and do not merit aggressive treatment.

- Type 2: These NETs occur in patients with gastrinoma. They rarely require aggressive treatment and resolve with treatment of gastrinoma.

- Type 3: Type 3 gastric NETs are sporadic. They are aggressive tumours and not associated with gastrin overproduction. These are removed with endoscopy or surgical resection depending on the size of the tumour.

Appendiceal and colorectal NETs

People with tumours in their appendix rarely have symptoms. Most appendiceal NETs are discovered when an appendix is removed for some other problem. It can sometimes cause appendicitis.

Most colorectal NETs present with bleeding, pain abdomen or change in bowel habits. Many are identified during Colonoscopy. Treatment of these tumours depends on the size and spread. Small ones can be removed by endoscopic modalities while larger tumours require surgery for their removal.

Pancreatic NET

Nonfunctional tumours rarely cause symptoms until late. They are mostly detected incidentally. They cause symptoms when they grow large. These symptoms could be pain abdomen, fatigue, unexplained weight loss, loss of appetite, jaundice, nausea, vomiting or lump anywhere in the upper abdomen.

Gastrinoma: Too much of gastrin causes stomach ulcer, pain abdomen and diarrhoea. This is known as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Insulinoma: Excess of insulin causes low blood sugar resulting in blurred vision, weakness, palpitations, anxiety, lightheadedness, sweating and confusion. These symptoms resolve on the consumption of high sugar food or drinks.

Glucagonoma: Overproduction of glucagon results in high blood sugar. The symptoms are skin rashes (necrolytic migratory erythema), diarrhoea, weight loss, frequent urination, headache, dry skin and mouth and increased appetite. It also leads to blood clots in the veins of legs and arms.

VIPoma: Abundance of vasoactive intestinal peptide causes large amounts of watery diarrhoea resulting in dehydration and low potassium levels in the blood. This results in muscle weakness, aching, cramps, confusion and excessive thirst.

Somatostatinoma: This results in high blood sugar. Symptoms are headache, unexplained weight loss, gallstones, diarrhoea, jaundice and steatorrhoea (foul-smelling stools that float).

Neuroendocrine tumours can also cause carcinoid syndrome in some patients. It manifests with skin flushing, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, vomiting, breathlessness, wheezing or asthma-like symptoms and heart failure.

Diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumours depend on the tumour type, production of the excess hormone, location of the tumour in the body, the grade of the tumour and stage of the tumour.

DIAGNOSIS

Various tests are done to detect and diagnose these tumours. The tests also help stage the disease i.e. to find how much the tumour has spread. The diagnostic tests include (not all the tests will be done in each individual):

Blood And urine tests:

Blood tests: Routine blood tests including complete blood count, liver function tests, serum electrolytes, blood sugar levels etc. are done.

Urine test: In suspected cases of carcinoid syndrome, 5-HIAA amount is checked in a 24-hour urine sample.

Tumour markers: Chromogranin A is a tumour marker, whose level in the blood is increased in many patients with NETs.

Blood tests for specific tumour types: Level of various hormones secreted by functional pNETs is checked in the blood.

Conventional cross-sectional imaging

Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CE-CT) scan

In this, the patient is placed in a scanner and beams of X-rays image the inside of the abdomen from all sides. These images are then computer-processed giving an accurate representation of inside organs. These images are enhanced with an injection of contrast into the blood circulation.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI)

It is an investigation similar to a CT scan. However, instead of X-ray beams, strong magnetic fields and radio waves are used to acquire images.

Endoscopy

It is a procedure in which a camera mounted, flexible and lighted thin tube is passed into the intestine, seeing the inner lumen. The camera is connected to a monitor which helps the endoscopist see the images. The procedure can be an upper GI endoscopy which helps see the inside of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum or lower GI endoscopy (colonoscopy) for colon and rectum. The endoscope can not reach the small intestine where most of these neoplasms occur. Capsule endoscopy shows the small intestine from inside. In this patient swallows a capsule with a tiny camera. The capsule then takes images of the inside of the intestine as it Travels and relays them to a device which records them. Another option to see the small intestine from inside is double-balloon enteroscopy. The choice of the procedure depends on the suspected location of the tumour. If any suspicious areas are seen small, pieces can be removed (biopsy) for examination under a microscope.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

It is an ultrasound of abdominal organs from inside. A special transducer mounted endoscope is used. It gives accurate images and helps us see and characterise the lesion. It shows how much the tumour has grown and whether the adjacent lymph nodes are enlarged. Besides, tissue or fluid can be aspirated from the lesion, a procedure called fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). It is examined under a microscope for the type of cells and various tests can be run on the fluid to find out the nature of lesion.

Biopsy

Biopsy means sampling a small part of a tumour and examining it under a microscope by a pathologist. The decision to do a biopsy in pNETs is complicated. It is not required in many cases where a clear cut decision to operate can be made. However, many times a biopsy is required to know the type of tumour, its grade and its differentiation.

Functional imaging studies (nuclear medicine imaging)

For these studies, radioactive tracers are injected, and they bind to the tumour. The patient is then scanned with a special scanner which shows the radioactive part lighted up, thus showing the tumour.

Octreoscan:

Historically indium-111 (111In) pentetreotide SSTR scintigraphy (SRS) linked octreotide was one such agent. It is no longer used as better scans are now available.

PET-CT

Two types of tracers are used for PET-CT of neuroendocrine neoplasms

- Gallium-68 (68Ga) DOTATATE, DOTATOC or DOTANOC

- 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)

These tracers are injected, bind to the tumour and then the patient is imaged with a dual scanner. The images are computer combined with CT images, giving us a CT image with bright tumours.

These scans also help to differentiate the grade of the tumour. Slow growing NETs (Grade 1 and 2) light up on DOTA scan while fast-growing (grade 3 NET and NEC) ones on FDG scan.

STAGING

Staging is a systematic way to describe the extent of disease. It tells clinicians about the local and distant spread of disease and helps them plan the treatment. It also predicts the outcome of treatment, a lower stage is associated with a better outcome.

Tumours are broadly classified into:

Localised - tumour is limited to the organ in which started

Regional spread - the tumour has grown to nearby lymph nodes or has come out of the Wall of the organ in which it started

Distant spread - the tumour has spread to organs which are not near the organs where the tumour started. When cancer has spread to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. The cancer cells break away from the primary tumour and spread through one of the three ways. It can spread through the bloodstream, lymphatic system or directly through the tissue.

TNM (tumour, node and metastasis) classification

Developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is used for exact classification of stages and spans from I to IV.

The extent (size) of the tumour (T): size and number of the tumour? Has cancer reached nearby structures or organs?

The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes? And to how many?

The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the peritoneum or lungs?

In NET staging, besides this, grade, differentiation, hormone production and symptoms are important parameters which guide the treatment.

TREATMENT

The prognosis and treatment options depend on the tumour type, location of the tumour, extent of spread of the tumour and the patients' age and general condition. Tumour grade and differentiation are important factors which determine the clinical behaviour of these tumours.

Treatment of localised tumour - Curative surgery

For nonfunctional tumours.

Potentially curative surgery to remove the tumour: When the disease is localised, has not spread to organs away from the origin and can completely be removed by surgery. Complete removal of the tumour to healthy margins is R0 resection. Besides the tumour bearing organ or part of it, adjacent lymph nodes are also removed. When it's not possible to remove a tumour with surgery, it is called an inoperable tumour. Sometimes inoperability is known only after starting the surgery.

Type of surgery

The surgical procedure depends on the location of the tumour.

Pancreas

For small tumours in the pancreas, enucleation is done. In this only the tumour is removed.

For tumours in the pancreatic head or large tumours of the duodenum, Whipple procedure or pancreaticoduodenectomy is done.

For tumours in the body and tail of pancreas, distal pancreatectomy is done.

For small lesions in the body of the pancreas, occasionally central pancreatectomy is done. In this only, the central part of the pancreas is removed and both the head and tail of the pancreas is preserved.

For cancers that have spread throughout the pancreas, total pancreatectomy is done.

Stomach

For tumours of the stomach, the options are resection of the tumour or removal of part of the stomach called partial gastrectomy. Tumours which are limited to the inner layers of the stomach wall can be removed endoscopically by snare polypectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

Small intestine

Tumours of the small intestine are removed by resection of the involved intestine and joining back the cut ends.

Appendix

For smaller tumours of the appendix, an appendectomy is sufficient. While for larger tumours, a part of the colon also needs to be removed as in right hemicolectomy.

Colon and rectum

Tumours of the colon are removed by Endoscopy if they are tiny. Larger tumours are removed by resection of the involved segment of colon. These surgical procedures are called colectomy and can be a right hemicolectomy, transverse colectomy, left hemicolectomy, sigmoidectomy, anterior resection, low anterior resection or abdominoperineal resection. Most of these procedures can be done laparoscopically.

Liver resection

Grade 1 and 2 tumours even if metastatic to the liver can be cured by removing the involved part of the liver along with the primary tumour, provided the remaining liver is large enough. Removal of part of the tumour bearing liver is called liver resection or hepatectomy.

A liver transplant can also be considered in rare cases.

Palliative surgery

Large tumours produce symptoms because of their bulk, by blocking the intestine or stomach and not letting the food and intestinal content to pass through. In such cases bypass surgery may be required.

Surgery for functional tumours

Debulking surgery for functional tumours: if it's possible to remove the bulk of the disease. It Will reduce the symptoms and improve quality of life.

treatment of Advanced tumour

Somatostatin analogues

Somatostatin is an inhibitory hormone in the body. It is a hormone which decreases the release of various other hormones. Somatostatin analogues such as octreotide and lanreotide Reduce symptoms and halt the growth of the tumour.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. They help stop the growth of the tumour by either killing the cells or stop them from dividing. Neuroendocrine tumour chemotherapy is generally administered to grade 3 tumours or neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Targeted therapy

It uses tumour's specific characteristics such as genes, proteins and blocks their growth. Everolimus blocks a protein called mTOR and Sunitinib Blocks several tyrosine kinases and stops new vessel growth hampering the blood supply of the tumour. Thus they stop the growth of tumours.

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT)

Used only for somatostatin receptor-positive neuroendocrine tumours. The radiolabeled peptide binds to somatostatin and enters the cells. Lutetium (177Lu-dotatate) or yttrium 90 ()90Y) are used to deliver radiation only to cancer.

Embolization or ablation

Tumours which have spread to the liver or lung are treated by embolization or ablation. Embolization means blocking the blood supply of the tumour. A catheter is passed into the vessel supplying the tumour, and it is blocked with small particles and other agents. Chemotherapeutic agents and radioactive beads can also be delivered directly into the tumour during this, called chemoembolization or radioembolization.

Ablation uses extreme heat or cold to kill the tumour cells. This is best for small tumours which are less than 2 cm. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses high-frequency radio waves to generate heat and kill the tumour. In this procedure, a probe is inserted into the tumour guided by ultrasound or CT scan and the radio waves are generated which can read the heat and kill the tumour. Microwave ablation uses microwaves to generate heat and kill the tumour. Cryoablation or cryotherapy kills the tumour by freezing it with a metal probe. Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) can also be given into the tumour killing the cells.

External beam radiotherapy

Radiation therapy uses high energy X-rays to kill cancer cells. It can be an option for those who can’t undergo surgery. It may also be administered to patients whose tumour was not completely removed at the time of surgery.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis means the overall chance of recovery from the tumour. The prognosis is measured in terms of survival rates (usually 5-year). It indicates about the percentage of patients who will be alive five years after they were diagnosed with the disease. In midgut NET 5-year survival rate for low-grade, intermediate grade and high-grade tumours were 79%, 74% and 40%, respectively. 5-year survival rates of 75% 62% and 7% were reported for Grade 1, Grade 2 and Grade 3 pNETs, respectively. These numbers are much better compared to many of the gastrointestinal cancers we treat.

Stay Alert! Stay Healthy!

Wish you a speedy recovery!